It was only recently that I learned that school kids—many,

if not most of them—were no longer being taught how to write in script. The

contemporary educators call it cursive script. I must admit to being stunned at

the news that penmanship instruction has seemingly gone the way of the beeper,

typewriter, and Rolodex. It’s something I assumed was in the “here to eternity”

column—infinite like the barber profession, Coca-Cola, and cat litter.

I appreciate, of course, that this is an advanced

technological age we live in, where the physical act of writing a letter by

hand—to someone or some entity—is quite rare, just as note taking at school or

at the office is. But—as I recall from my school days—writing by hand in a

penmanship all my own took my writing to a higher level, even when it was less

than artistic. I couldn’t conceive of printing out an essay during

those years. Printing the individual letters of the alphabet to form words,

instead of in script, would have taken a whole lot longer and, too, taken away

a fair chunk of my individuality. Sitting down, putting pen to paper, and

writing by hand in script stimulates the brain in ways not realized when

banging away on a keyboard. I read where students who took notes in their own cursive

writing hands, rather than on their laptops, had a much better recall of

the materials. Makes perfect sense to me.

Okay, so the handwriting is not on the wall anymore. I

understand. Who needs a personal signature when our eyeballs can be scanned?

But I just thought of something. I collected all sorts of things as a boy,

including autographs. I’d get players at the ballpark to sign my scorecard if possible. And it was all very exciting. Acquiring an obscure journeyman’s

signature was even a thrill. Fast-forward a couple of decades from now and the

autograph, I guess, will be reduced to something akin to a caveman’s mark.

Anyway, in expressing my surprise at penmanship’s untimely swan song,

I was apprised of this college-aged young man who cannot read anything written

in script. It's all Greek to him and might as well be hieroglyphics—because he can’t decipher a

word of it. And I suppose he is not alone in this affliction. For starters,

let’s rule out a career as a historian. Fifty years from now, maybe, he

could cut the mustard and research a biography of someone from this Pokemon Go

day and age of ours by combing through e-mails, tweets, and Facebook posts, but not now.

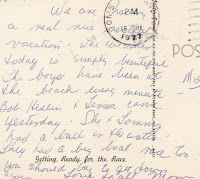

So, yes, it’s going, going, gone—the postcard from a friend or

family member written in that familiar hand. The grammar and high school tests

handwritten by the teacher and mimeographed on top of that. The teacher

commentary with that personal touch on the report card—the one that came in a

brown envelope where we wrote in script our names and classroom numbers.

All I can say is that if John Hancock were alive today he’d be rolling over in

his grave. And I’d bet the ranch that most folks who don’t write or read

script haven’t a clue who John Hancock was.

(Photos from the personal collection of Nicholas Nigro)